By Brad Broberg

Locked in the basement of the Burke Museum, he's the world's oldest political prisoner.

Alarms provide security. Officials record his every move. No one sees him alone.

Native Americans call him the Ancient One, but to the rest of the world he's Kennewick Man, the object of a bitter tug-of-war to determine who owns the past.

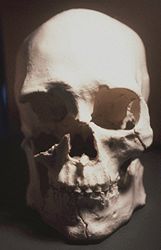

This plastic casting of the skull of Kennewick Man was shown at a 1997 press briefing.

Considered a landmark discovery, his 9,000-year-old skeleton arrived at the University of Washington in 1998 when the federal government picked the Burke Museum of Natural and Cultural History as his home until the courts determine his future.

Under normal circumstances, hosting a find like Kennewick Man would have been a coup for the Burke. But these weren't normal circumstances. Not with a group of prominent scientists suing the federal government—and by extension five Pacific Northwest tribes—over control of the remains.

"We did not solicit this," says Julie Stein, who was curator of archaeology at the Burke when the bones were transferred from the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Richland. "It was not a political arena that anyone would choose." Nevertheless, given the Burke's status as the state's official natural history museum, "it was the right thing to do," says Stein.

When it comes to Kennewick Man, doing the right thing has never been easy. More than four years have passed since hydroplane fans stumbled across his skull along the Columbia River, and still his ultimate fate—ongoing scientific examination or repatriation to the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla—remains hostage.

The tribes did gain ground this fall when the federal government—responding to questions posed by a federal judge—reaffirmed an earlier decision that Kennewick Man ought to be repatriated. Even so, the Ancient One's final destiny won't be known until the lawsuit is settled.

"I think it's a big victory for us [but] the scientists aren't going to give up," says Jeff Van Pelt, director of cultural resources programs for the Confederated Tribes.

Considering the injuries he sustained during his lifetime, this is not Kennewick Man's first scuffle. However, it's safe to assume no earlier fight involved the same volatile mix of race, religion, politics and science that supercharge the current conflict—a conflict that challenges the ethics of science, the validity of federal law and the very definition of Native American.

| On the Web: Burke Museum Kennewick Man Exhibit |

Go To: Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4

- Sidebar: Guarding the Man

- Return to December 2000 Table of Contents