A Civil Action, Part Four: World War II Brings Internment, Financial Ruin

That's when Yamashita, no longer a fresh school graduate but a 47-year-old businessman, committed his second major act of rebellion.

He and a fellow immigrant named Charles Kono filed articles of incorporation to create the Japanese Real Estate Holding Company. The xenophobic Seattle Star reported that the partners had gained control of "rich agricultural lands" in the White River Valley, where more than half the state's Japanese farms were located.

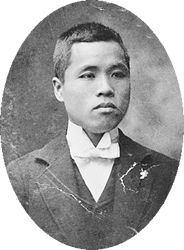

A young Yamashita poses for this formal portrait, perhaps taken at the time he attended the UW. Photo courtesy of the Takuji Yamashita Photograph Collection, University of Washington Libraries.

When Secretary of State J. Grant Hinkle refused to register the corporation, Yamashita, this time, did not have to fight alone. He had an eminent New York attorney on his side, George Wickersham, a former U.S. attorney general who'd been hired by the Pacific Coast Japanese Association on behalf of a Hawaii resident named Takao Ozawa. Fearing that Ozawa might lose on a technicality, Wickersham needed a backup case. Thus did Yamashita help lead the Japanese-American counterattack against exclusion.

Bringing both cases to the U.S. Supreme Court, Wickersham borrowed some of Yamashita's legal arguments from 1902—that Congress had singled out the Chinese for exclusion but was silent on other Asians, that Japanese immigrants had demonstrated their ability to fit into American society, and that the Founding Fathers' vision of equal opportunity was "the highest ideal of Americanism."

The outcome was the same as in Olympia two decades before. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously against Ozawa, and then cited that decision in rejecting Yamashita: Someone of the Japanese race and born in Japan was not entitled to be a naturalized citizen of the United States.

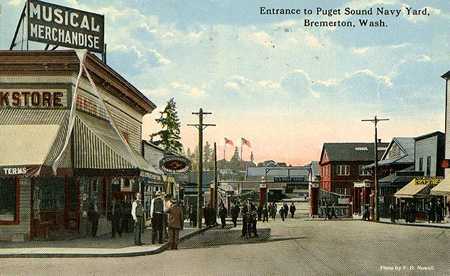

Even this setback did not seem to shake Yamashita. When the Navy took over his Togo Hotel to expand its shipyard, he bought the nearby Rainier Hotel. A couple of years later, he opened the People's Café where he kept on feeding workers hungry from overhauling the West Coast fleet.

An old postcard, from ca. 1917, shows the entrance to the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, in Bremerton, Wash., near where Yamashita owned the Togo Hotel and, later, operated the People's Café. Image courtesy Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries.

Yamashita had an ability to move on from even the most staggering losses, said historian Ronald Magden, '64, who deserves much of the credit for Yamashita's rediscovery. While researching his 1998 book on Japanese settlement of Pierce County, Magden found that interviewees who'd met Yamashita in his later years knew little of his courtroom showdowns.

"He never talked about it again, he just walked away," Magden said. "I think that's absolutely key to his character."

That's what probably enabled Yamashita to endure. In the mid-1920s, he buried a son and a daughter. What remained was the nuclear family of Takuji, Ito and Martha, a daughter born in 1910. Of fragile health like her siblings, Martha attended the UW for a year but dropped out in 1931 because of tuberculosis.

For all the heartbreak, this clan was a vibrant threesome. Fred Ohno remembers them as "a tremendously happy family" living on 20 acres of leased waterfront property in the town of Silverdale, a place where they could raise oysters and strawberries and let Martha inhale revitalizing country air.

"Takuji never complained," said Ohno. "He was never bitter."

Another teenage pal of Martha's during the '30s, Yoshiye Iwamaura, recalls the Silverdale spread as a social nexus for the region's Japanese, who would ferry from Seattle for beach parties featuring roasted clams and sukiyaki.

But it wasn't all play. Takuji joined the night oyster-harvesting crews after locking up the People's Café. Ito cleaned and bottled the mollusks, and the outgoing Martha sold them to shopkeepers in Bremerton.

Except that after Japanese planes bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Bremertonians wouldn't buy from Martha anymore, according to her brother-in-law, Sam Nakao. That was the least of the problems. Like 110,000 others of Japanese ancestry, the Yamashitas were soon ordered to internment camps. On July 24, 1942, the family locked up the dream house they had just finished building in Silverdale, with a view that seemed to touch the mountains. They never saw it again.

As a distinguished Issei, or first-generation immigrant, Yamashita was elected a block leader by fellow inmates of California's Manzanar camp, Iwamura said. But the internment was the blow that finally weakened his spirit. Unable to pay their bills during three years locked inside three camps, the family lost all its holdings. Takuji Yamashita, the brilliant scholar, returned from the camps to survive as a housekeeper for a widow in West Seattle, Nakao said. This lasted until 1957, when daughter Martha died, childless. Within a month, Takuji and Ito returned to Yawatahama for good. Two years later, Takuji, too, was dead.

| On the Web: HistoryLink.org Timeline entry |