Chapter Two: Sojourn to the East

Wiley had spent two years at Cornish and another year and a half performing in a small dance company when she was invited to apply for a position in the Dance Department at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts. The thought of leaving her beloved Northwest was daunting, but Wiley jumped in with both toe shoe-clad feet. She decided to make her very first visit to New York City when she went east for the interview.

In New York she had another revelation: she attended modern dance performances of the classics in the field. Suddenly, she became aware that although she had been exposed to theater history, music history and art history, she knew nothing of dance history, at least outside of ballet. That knowledge, it seemed, was confined to the East Coast.

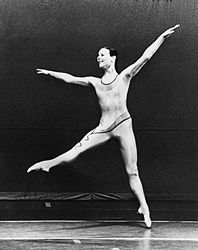

Wiley dances in a New York City production in the early 1990s. Photo courtesy of Hannah Wiley.

"I really felt cheated," she says. "That felt wrong to me, to have gone to a huge state school with a wonderful reputation and not to have seen those dances, not to have them even mentioned." It was an oversight she would later work to correct.

Wiley was hired by Mount Holyoke, and a year later, when the small department's chair left, Wiley succeeded her. A few years later, still in her 20s, she became chair of a consortium known as the Five College Dance Department, made up of Mount Holyoke, Hampshire, Amherst, Smith and the University of Massachusetts.

"We were a department in name only," remembers Hampshire Professor of Dance Rebecca Nordstrom. "What Hannah did was to make it all function like a department." That meant, Nordstrom explains, everything from working with top administrators of all the schools to getting the course numbers of comparable classes aligned so that students could take classes at any of the schools and their transcripts would look right.

"Hannah has a tremendous amount of energy and a great ability to work with all kinds of people," Nordstrom says. "What's amazing is that she seems to be equally skilled at administrative work and creative work. Even as department chair she never stopped performing and choreographing."

When it was suggested she come up for early tenure, Wiley was advised to get her master's degree. Enrolled at NYU, she used the degree program as a chance to study anatomy, biomechanics and physics, at last learning the science behind the movements that she had first encountered at the UW. As she had expected, it made a difference.

"I completely revamped my teaching after that," she says.

One recipient of all she was learning was Maria Simpson, '96, then a 12-year-old performer in a dance company that Wiley sometimes choreographed for. "Even at 12, I knew that meeting Hannah was life-changing for me," says Simpson, now an assistant professor of dance at the UW. "No one I had encountered before was like her. She could explain why a certain position of the body makes a movement easier. She made ballet fun for the first time."

Simpson explains, using the classic dancer's high kick as an illustration. All dancers, she says, want to "get their legs up to their ears." But often ballet teachers don't explain how that's most easily accomplished. "If you understand how the hip socket is made, you know that by putting the body in a particular position, one bone gets out of the other bone's way and it's easier," Simpson says.

There is, however, a lot of resistance in the ballet world to such teaching. "They think somehow that the science takes away from the art," Simpson says. "People like Hannah are not popular with the ballet establishment."