N A BEAUTIFUL, MAY MORNING, SARAH Reichard wondered who could be calling her at 5:30 a.m. She had no idea that the ringing phone was the first warning that her professional life was being turned upside down.

N A BEAUTIFUL, MAY MORNING, SARAH Reichard wondered who could be calling her at 5:30 a.m. She had no idea that the ringing phone was the first warning that her professional life was being turned upside down.

Reichard's colleague, Linda Chalker-Scott, left a hurried message on the answering machine: "The lab is on fire and I'm going down there." Reichard remembers feeling sorry about the lab fire, "but the importance didn't really hit me," she says. She leisurely fed the cat, then called Chalker-Scott's husband to ask how bad it was. "He said to turn on the TV," Reichard recalls. "The first thing I saw was the image of what looked like my office, up in flames."

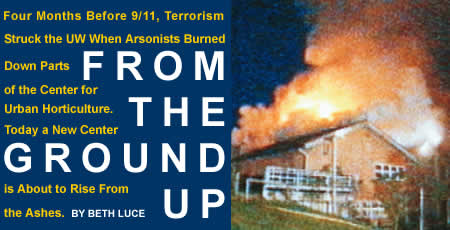

Sometime after 1 a.m. on May 21, 2001, members of the Earth Liberation Front (ELF), an underground "eco-terrorist" group, broke into Merrill Hall, the oldest and largest of several buildings at the Center for Urban Horticulture. Part of the College of Forest Resources, the center sits near Union Bay and the Montlake parking lot, a testament to the region's love of gardening, since all the buildings were financed with private funds.

That night, the ELF visitors left a calling card-a bomb made from a bucket of gasoline, a child's rocket and a kitchen timer. A little after 3 a.m., it exploded in a giant fireball.

The resulting fire burned Merrill Hall beyond repair; severely damaged the Elisabeth Miller Horticulture Library; ruined the work space of 50 research faculty members, graduate students and staff; destroyed one-quarter of the world's population of an endangered plant species; consumed decades' worth of academic literature; closed cooperative extension offices; and melted hundreds of slides, including some illustrating the step-by-step recovery of Mount St. Helens.

"It's still hard to believe that something like this happened to us," says Reichard, an assistant professor of ecosystem sciences. "We teach about horticulture and sustainable landscaping and conservation and restoration. Who would want to destroy that?"

Today, visitors to the center can see winter color in the Goodfellow Grove, the McVey Courtyard and the Seattle Garden Club's Entry Garden. They can see people writing notes about the various flowers and grasses in the Soest Garden. People are using the "new" Elisabeth Miller Library and the Hyde Herbarium. The Plant Answer Line is ringing, a Master Gardener is answering a garden pest question; there might be a public lecture sponsored by the Northwest Horticultural Society in NHS Hall; and students are attending classes in restoration ecology in Douglas Hall.

That the center would recover so well would have surprised Reichard on the day of the fire. When she neared the center, three hours after the explosion, 50-foot flames were still shooting into the sky. She found fellow professor Chalker-Scott, and they stood, horrified and unbelieving. "For academics, this isn't just an office. It's our world," Reichard says. "A huge portion of my life is in my office and my lab." When he heard the news, H.D. "Toby" Bradshaw, a plant geneticist who worked at the center, knew right away why the building was on fire. "I've been around enough of these terrorism events to recognize the signature," he says.

Bradshaw, who has since been appointed associate professor, caught the unwanted attention of radical environmental groups for his work with the genetics of poplar trees. That research, he says, is only a small part of his work, which also includes researching the evolution of monkey flowers and experimental genetics in a mustard plant. He works with poplars because they grow quickly, making them easy to study. He's looking for genes that, for instance, control the tree's growth, repel pests and create fewer knots in the wood. As a practical application to his research, plantations of fast-growing, disease-resistant poplar trees can be used to supply lumber and paper as an alternative to logging forests.

Go To: Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4- Sidebar: Surviving the Flames

- Return to December 2002 Table of Contents