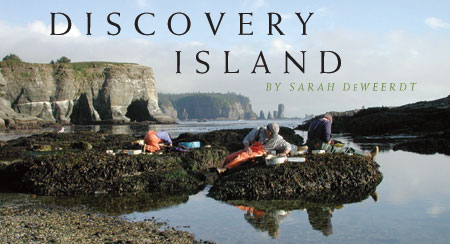

Environmental Science Took a Decisive Turn on an Obscure Island off the Northwest Corner of Washington. The Way We Look at—and Try to Save—Our World Has Never Been the Same.

For a quarter-century, whenever Robert Paine visited Tatoosh Island, his routine was always the same. At low tide, he would go down to a slope of rock, nicknamed “the Glacier.” Stepping carefully over the mussel bed, he would pry all the starfish he could find from their prime feeding ground, then dump them unceremoniously into the Pacific.

After a short while, Paine would be sweating inside his rain gear and rubber boots. His thick, square glasses were often blurred by salt spray and rain—the windswept island off Washington’s Cape Flattery gets an average of 100 inches of rain a year. But he would not stop until the mussel bed had been picked clean of the starfish, a large, bright-orange or purple species known as the ochre sea star.

Sometimes there were a hundred or more to remove. For a time, whenever Paine handled the starfish, the skin would peel off the tips of his fingers—possibly an allergic reaction. He has tossed away thousands of starfish in his lifetime.

Such behavior might seem bullheaded or outright nutty, but in reality what Paine was doing was just good science. Throwing starfish was part of one of the longest marine ecological experiments ever conducted, a 25-year investigation of how the loss of a top predator would affect the rest of the rocky intertidal ecosystem. Such work has made Paine, now a professor emeritus of biology at the UW, one of ecology’s most prominent thinkers, honored by the Ecological Society of America, the American Society of Naturalists and the British Ecological Society.

His fame rests on two major scientific achievements: investigating how interactions between species hold the strands of food webs together—especially his development of the “keystone species” concept—and moving ecology from passive observation to active experimentation in natural environments. For nearly four decades, Tatoosh Island has been the living laboratory where Paine has developed and refined his achievements.

It is a forbidding place. The 20-acre island sits where the Strait of Juan de Fuca meets the Pacific. Traveling northwest, it is the last piece of land in the “Lower 48,” subject to gales with winds that can reach 100 miles an hour. In winter, when 25-foot waves are common, the only way to get there is by helicopter.

Yet the island also possesses an extraordinarily diverse intertidal environment. In addition to its abundant marine life, the island has a major seabird nesting colony and is a stopover point for migratory birds. “It’s a handsome spot,” says Paine, who began working on the island in 1968. “It’s a spot I know and love, and it’s packed with all kinds of interesting biology.”

Tatoosh was once the site of a Makah summer village, where tribal members dried racks of fresh-caught fish and launched whaling canoes. A lighthouse, guiding mariners through the perilous entrance to the strait, began operating in 1857. In the early 20th century, the federal government had a weather station on the island. During World War II, the Navy used it to listen to Japanese radio transmissions.

Today, the Makah, who own the island, allow few outsiders to visit. This isolation, and the stretch of rough water separating the island from Cape Flattery, ensures that the environment remains pristine and experiments can run unmolested. By giving the scientists access to the island over nearly four decades, the Makah have made possible long-term ecological studies that are vitally important but rarely possible.

Over the course of 37 years, Paine and a shifting community of students and colleagues have studied nearly every major group of the island’s intertidal species—sea anemones, sponges and weird seaweeds, to name just a few. They have formed, tested and sometimes dismantled a variety of ecological theories. As a result, Tatoosh is one of the world’s most studied marine environments, and one of the most famous field sites in all of ecology. Aquatic and Fishery Sciences Professor Julia Parrish, who has been studying seabirds on the island for 15 years, calls it “hallowed ground.”

Go To: Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3