|

When he began his research at WSU, Taylor found the Pacific Northwest particularly fascinating. From the founding of Seattle and Portland, African Americans were not the largest group among peoples of color-it was Asian Americans. "That changed the racial dynamics," he says, "It complicated matters."

During the 1880s and '90s, when the gains from Reconstruction were crushed in the South, blacks told their friends and relatives "how free the air is" in the Northwest. Black newspaper editor Horace Clayton Sr. wrote, "We are the new frontier and thousands of negroes come to this part of the country and stand up like men and compete with their white brothers."

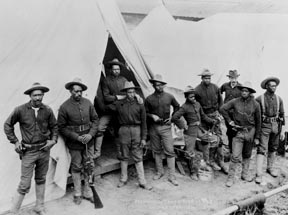

African-American soldiers line up in front of their tents at Fort Lawton in Seattle prior to being sent to China during the Boxer Rebellion. Photo courtesy of UW Libraries Pacific Northwest Collection.

While conditions were certainly better than in Mississippi, blacks suffered from what Taylor calls "racial myopia." An 1879 editorial in the Daily Intelligencer (forerunner to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer) stated, "There is room for only a limited number of colored people here. Overstep that limit and their comes a clash in which the colored man must suffer."

Taylor also faults the African Americans of that time for failing to criticize the treatment of the Chinese population-including the expulsion of all Chinese from Seattle in 1886.

"Black folk had nearly as much fear and prejudice of the Chinese as the whites," Taylor says. In his research on Seattle's Central District, he even came across a local African American who was a member of a "nativist" society aimed at keeping Asians out of the United States.

His research into Seattle's past resulted in a groundbreaking history of Seattle's Central District, The Forging of a Black Community, published by UW Press in 1994.

What these stories illustrate, Taylor says, is that racism and prejudice in the West were "extremely malleable. There was a tremendous amount of fluidity in the West," he notes. "Everyone was reinventing oneself."

Taylor explores these multicultural interactions in his next works. His is the co-editor of anthologies coming out next year on African Americans in California and on African-American women in the West. He is also writing the first historical text on African Americans in the West during the 20th century. Yet another project in the planning stages is a series of anthologies, Peoples of Color in the Pacific Northwest, co-edited by UW Professor Erasmo Gamboa.

As the United States evolves in the new century, it will become even more of a multicultural society, Taylor notes. In his view, there are two paths to the future, both found in the Western experience. "Seattle is on one path, where there is a shared sense of community. In Los Angeles, we see the other path, where there are four or more separate groups competing for power.

"I don't want us to pat ourselves on the back because Seattle is so much better," he adds. "It's just different. It's not like New York, Chicago or Washington, D.C. Demographics is everything. I would like to suggest that Seattle's liberalism would not have existed had the African-American community been 10 times as large as it was."

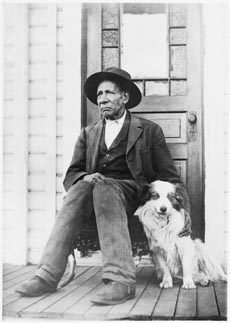

The black founder of Centralia, George Washington, is seen late in life resting on his porch with his dog. A free African American, Washington came to the land along the Chehalis River in 1852, to escape persecution in Missouri, Illinois, and Oregon. He ended up in Washington Territory because he had no legal rights in Missouri, Illinois had a law requiring blacks to post a cash bond of $1,000 "for good behavior," and Oregon prohibited blacks from settling in its territory. A park and a library in Centralia are on land that he donated to the city. Photo courtesy of the Washington State Historical Society, Tacoma.

Taylor is finally living in the city he has studied since the early 1970s. His first encounter with Seattle's Central District came shortly after his WSU student's challenge to learn more about blacks in the West. He began to gather oral histories of blacks living in the West and came to do some Seattle interviews.

He gathered 40 to 50 interviews and realized that "this is a story that needs to be told." Two years later he helped win a quarter-million-dollar grant from the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare to produce a five-part "docudrama" about the black experience in the Pacific Northwest.

"It was called South by Northwest, and it came out a year before Roots would popularize African-American history on TV. In fact, our director, Joseph M. Wilcots, was later one of the directors of photography on Roots," recalls Taylor, who was historical adviser and assistant director.

|