Rice also questions omitting fringe benefits from wage growth analyses, especially when you consider the increased value of medical coverage. "It really makes a large difference in how the statistics look when you put health insurance in," he says.

Finally, he challenges Morris' allusion to the arrival of Reaganomics as a driving force behind slumping wage growth. He says the decline of unions is a result of the changing nature of the economy—a change that began long before the Reagan Administration.

But there is one conservative group that might take comfort from the trends found in Divergent Paths—those who blame affirmative action laws for the decline in white male income. However, those folks are missing the point, says Morris. "It's not affirmative action that caused the loss of the blue-collar aristocracy," says Morris. "Women and minorities haven't taken those jobs. Those jobs are gone."

For those starting their careers in the late 1960s, 56 percent benefited from high wage growth (red) during the first 16 years of their work life. Those with medium growth (green) totaled 32 percent while low growth workers (blue) totaled only 12 percent. For those starting their careers in the early 1980s, only 37 percent benefited from high wage growth (red)-while the medium growth (green) group rose to 36 percent. The low growth group (blue) more than doubled to 28 percent. Source: divergent Paths: Economic Mobility in the New American Labor market, Figure 7.1.

With manufacturing jobs falling 41 percent between 1972 and 1996, four out of five Americans now work in the service sector, which offers far more low-paying jobs than high-paying ones, according to studies cited in Divergent Paths.

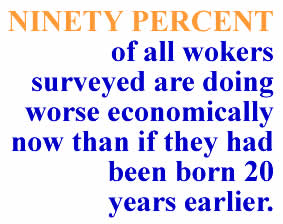

By themselves, those statistics might not scare anyone, but they're joined by darker trends. Before crunching any numbers, Morris and her colleagues had assumed that the service sector's appetites were being satisfied by young people fresh to the work force. If past patterns held true, those jobs would become springboards to better employment.

But past patterns have unraveled. Morris and her colleagues found that more and more workers are trapped in the service sector's lowest paying jobs-cashier, data entry, telemarketing—which ironically are also its strongest growing sectors.

Why are those jobs so sticky? Because restructuring has washed away many roads to upward mobility—not just in the service sector but across numerous industries, says Morris. For example, as companies outsource more jobs to specialized subcontractors and flatten their management, they provide fewer chances for employees to rise from within or gain new skills they can exploit elsewhere, she says.

Economics Professor Lundberg doesn't necessarily disagree with that conclusion, but does label it speculation. "We can't see the operations of career ladders in the data," she says. "It's conjecture. It may not be inaccurate, but the evidence isn't there."

Morris admits she and her colleagues may seem like party poopers to have painted such a bleak picture during a time of economic prosperity. But they say the message needed to be sent—even if it's hard to hear over the clamor of the ticker tape.

"We hope to introduce a balancing perspective into current policy discussions," they write, "which have tended to be swamped by the economic boom and the needs of the stock market—for example, lack of wage growth is now applauded as an economic indicator. It is time to put long-term trends in workers' welfare back on the table."

The big question, says Lundberg, is whether anyone has the political will to do so. Right now, the answer appears to be no as most people remain mesmerized by the chance—no matter how slim—that they can hit the jackpot in the new economy. "To Americans, the potential of winning big outweighs the risk of losing when we think of public policy," says Lundberg.

Morris cites two ways in which the country has so far "managed itself around" declining wage gains. "People have futures and they continue to mortgage them," she says. Plus the migration of women into the workforce has helped keep median household incomes steady. But neither Band-Aid can last forever if wage gains remain stagnant. And both come with a price as people saddle themselves with consumer debt—the average household with credit cards carries a monthly debt of $4,000—and devote less time to family life, notes Morris.

Unlike the first National Longitudinal Survey, the second is continuing to track participants into their 40s and 50s and has valid data on women and minorities. Plus a third survey of a fresh cohort was launched in 1992. Together, those additional statistics will help prove whether the stagnant wages and growing inequality Morris and her co-authors documented were blips on the radar or permanent features of the new economy.

"There's a group of people who don't think there's anything wrong ... it's just the market giving everyone what they deserve," says Morris. "But it is not clear why people in this generation deserve so much less than their parents."—Brad Broberg is a free-lance writer in south King County whose Dec. 2000 Columns article, "Bones of Contention," won two feature writing awards.