"That is the larger megasystem that provides not only water for drinking and industry and agriculture, but defines the climate that we and others experience. We must be very careful about water control engineering when it short-circuits-or even destroys-the water cycle."

An immediate problem with nearing the limits of our water resources is that we have "less margin of safety to cope with the unexpected," says Miles, a founding member of the Climate Impacts Group, a research group based at the UW that strives to help businesses, agencies and other organizations incorporate short-, medium- and long-term climate forecasts into their planning.

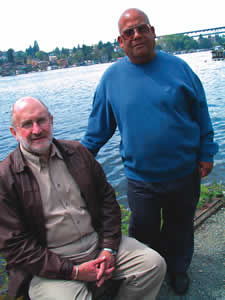

UW Fisheries and Public Affairs Professor Jim Karr (seated) and Marine Affairs Professor Ed Miles say the coming water shortages will dwarf past droughts. Scarcity has not been seen on this scale before, warns Miles. Photo by Kathy Sauber.

That applied approach is coupled at the UW with some of the nation's best research and teaching on climate, packaged last year under the new Program on Climate Change. UW climate researchers in the last decade have discerned or helped define the effects of a number of Pacific Northwest, North American and global climate patterns.

The more we know about El Niņo, La Niņa, the Pacific Decadal Oscillation and other climate cycles, the better our forecasts and planning, Miles says. For example in 1987 the region had a wet winter and spring, followed by virtually no rain from July through December. If we'd known that was the risk, Miles says, we might have instituted aggressive conservation measures that summer and avoided water supply shortages in the fall.

Miles says establishing a regional climate monitoring service would improve forecasts and help us learn what different climate cycles mean for the region. Another challenge is that water management is highly fragmented. No single entity is in charge of Columbia River water when droughts hit. Entities from the international level down to the county, private and tribal level can have conflicting goals, and standards for water quality and quantity across basins are often inconsistent.

Still the biggest challenge is planners and others who continue dealing, "only with population growth and the Endangered Species Act demands," Miles says.

Right now, says Naiman, if it weren't for the Endangered Species Act or the area's water problem would be a lot worse. "It's one of the strongest pieces of legislation we have for protecting the environment. Even that won't be enough in coming decades," he says.

Naiman says we're going to see unimaginable changes in the next 50 years if we continue on in the same ways.

"It's as if most people don't truly understand where their water comes from, how it's collected or how it is carried into their homes," he says. "Everyone should be knowledgeable about the soundness of the infrastructure and how water is treated, as well as understanding the broad ecological consequences of developing water supplies."

Using today's science to plan for tomorrow's water policies, taking personal responsibility for how we use resources like water and power, taking more steps to conserve and pursuing growth management are all possible ways out of this mess.

"The University needs to be relevant to these issues, to foster debates and discussions and to provide leadership in helping find solutions," Naiman adds.

Of course, scientists alone can't show the way. Politicians and the citizens who elect them have to have the courage to ask the right questions about how to solve this problem and, then, to implement the answer.

"Unlike other things that society depends on-such as supplies of energy, of minerals for industrial processes, even foods-no substitutes exist for most water uses," Karr says.

"Everyone needs a supply of fresh clean water every day." o A Washington native, Sandra Hines is a graduate of Washington State University and has worked 15 years for the UW writing about science and environmental news. She doesn't plan to water her lawn this summer.

- A Washington native, Sandra Hines is a graduate of Washington State University and has worked 15 years for the UW, writing about science and environmental news. She doesn't plan to water her lawn this summer.

Go To: Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3

- Return to June 2003 Table of Contents