For the first time, Malcom realized the magnitude of what she and other ethnic minorities (especially women) had been up against her whole life. Science education programs--run mostly by white men--often excluded minorities. And those that were set up to serve minorities favored men.

That led to a 1975 landmark report, "The Double Bind: The Price of Being a Minority Woman in Science." In it, Malcom documented that minority women were the victims of two problems: racism and sexism. The biggest outrage: educational programs geared toward minorities gave preference to men. She also found that the few minority graduate students or professors in academe weren't often incorporated into each department's culture.

"These issues were not part of the national agenda 15 years ago," says Angela Ginorio, a UW sociology professor and director of the Northwest Center for Research on Women.

So Malcom devoted herself to trying to make things right. As head of the AAAS Directorate since its establishment in 1989, Malcom--who manages a staff of 50 and an annual budget of $6 million--developed a wide array of programs advancing education in science, mathematics and technology at all levels, improving public understanding of science and greatly expanding the talent pool.

But like much of her life, it didn't come easy. Since traditional education wasn't doing the job, she wanted to go "outside the box" and reach out to minorities in their communities. She wanted to find other ways to teach science. She hit resistance at every turn, from people not liking her ideas to not having enough resources to carry them out.

"

My views about providing access to science for all were a hard sell for a while," she says. "Not everyone has agreed with the necessity of getting communities and parents directly involved inthe stuff of education reform."

Among her innovative programs is the Black Churches Project, which uses churches and church networks across the nation to bring science, environmental and health education to African American communities. Another is Proyecto Futuro, which connects science learning in the school, community and home by creating bilingual materials and demonstrating links between science and the Latino culture. She is also busy overseeing Kinetic City Super Crew--a radio adventure series with on-line, club and classroom outreach--as well as Earth Explorer, a CD-ROM multimedia encyclopedia of the environment.

She also holds workshops for teachers, has set up a network of deans at major research universities, and works with government leaders to secure enough science money for schools.

"She is as involved with driving policy from the top as she is with making certain her programs are heavily invested at the grass-roots," says Catherine Gaddy, executive director of the Commission on Professionals in Science and Technology.

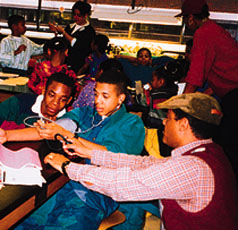

There is no better example than the nine Seattle churches where the Black Churches Project holds court on Saturday mornings. It isn't unusual for 40 or 50 neighborhood kids to turn out for science classes in the basements of such local churches as Bethel Christian and Greater Mt. Baker Missionary Baptist.

"The kids really get into it," says Millie Russell, assistant to the vice president of minority affairs at the UW and the local contact for the nationwide project. "There is so much interest in our neighborhoods that has gone untapped. Children love science projects, and we have to get the community involved even more."

Another creative idea of Malcom's was having high-school students tutor younger children in science. That was the cornerstone of a community science project funded by the Readers Digest Foundation. "It was effective because it showed that kids of all ages are very interested in science," says Terry Russell, executive director of the Association for Institutional Research. "Now the aim is to get parents involved."

Malcom never stops aiming high. She received the Reginald H. Jones Distinguished Service Award, the highest honor given by the National Action Council for Minorities in Engineering, in 1997 and directed the $10,000 prize to teachers in the beleaguered District of Columbia school system.

But grass-roots are only part of Malcom's approach. In addition to serving on the National Science Board, she is on the President's Committee of Advisors on Science and Technology and was chair of a task group studying labor and education issues for the Clinton transition team.

Malcom "has been a leader of championing the importance of ensuring that all students receive an outstanding science education," says UW Engineering Dean Denice Denton, the first woman dean of engineering at a major U.S. research institution. "Her work in explaining the importance of diversity in the science, math and engineering workforce has been pivotal."

But devoting herself to having that kind of impact has come at some personal cost. "What makes you think I ever unwind," she asks with a smile. "I have to work at it." Though she traveled a lot when her two daughters were young (they are now students at MIT and Duke), she says, "When my daughters needed to carry in the birthday cupcakes, I always baked. That was my penance."

Things are better now, but there is still so much to do in the push for science education for all, especially with new efforts to turn back affirmative action.

"Convincing people that we can all get further if we work in partnership on solving our education problems in this country continue to be a challenge," she says. "And the assault on programs to bring access to quality education in science, mathematics and techonolgy to all makes me feel that I am starting where I began."

But Malcom has never been one to give up. She didn't give up when she failed her chemistry quizzes, and she isn't about to now.

"The opportunity to reverse those trends are at hand," Malcom says, referring to data suggesting that interest in pursuing science and engineering majors is growing among minority freshmen.

"The next generation of science must necessarily draw on young people who are not generally see (and indeed often do not see themselves) as being in the present mix," Malcom wrote in a major piece for Scientific American. "Who will do science? That depends on who is included in the talent pool. The old rules do not work. It's time for a different game plan that brings new players off the bench."

Return to the beginning of "Coming Off the

Bench"

The UW's Alumna Summa Laude Dignata

Award

Send a letter to the editor at columns@u.washington.edu.