Sarason and Bricker couldn't have timed their study better. It comes amid heightened public, media and government scrutiny of the airline industry.

In the first nine months of 1999, the U.S. Department of Transportation received almost 16,000 complaints from air travelers—twice last year's rate. And the department estimates that for every complaint it receives, the airlines receive 400.

A recent customer satisfaction survey by the University of Michigan ranked airlines third from the bottom in a list of 34 industries and public services.

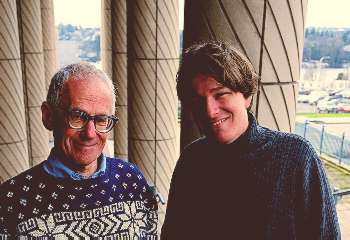

Psychology professor Irwin Sarason (left) and doctoral student Jonathan Bricker. Photo by Kathy Sauber.

Several web sites, including ticked.com and PassengerRights.com, are full of horror stories from passengers claiming to have been bullied, deceived and stranded by airlines.

Not surprisingly, 43 percent of the respondents to a Newsweek poll said flying has become "more stressful in recent years."

Congress considered passing a Passengers Bill of Rights last year covering such issues as lost baggage, unexplained delays and confusing fares.

Although the airlines managed to stave off legislation, they couldn't entirely wriggle off the hook. They signed an Airline Customer Service Commitment with Congress. The agreement required airlines to prepare customer service plans addressing 12 general areas—many of them related to the factors identified in the Sarason/Bricker Air Transit Stress Scale (ATSS).

The airlines submitted their plans in July and had to implement them by Dec. 15. But that's not all. The transportation department has assigned 19 auditors to prepare two reports—one due in June and the other in December—to gauge how well the airlines live up to their plans. Much of the content will be based on numerous flights each auditor will take.

Against that backdrop, Sarason and Bricker have enjoyed a lingering 15 minutes of fame. Newspapers, magazines and television stations have been steadily requesting interviews ever since the University sent a press release announcing their study in August.

"It's been constant," says Sarason. "At least every two weeks we get a phone call."

In one case, a TV station filmed Sarason and Bricker questioning passengers as they disembarked at Sea-Tac Airport. Even the New York Times inquired about a possible interview.

"Interestingly, we haven't heard from one airline," says Bricker.

That doesn't surprise UW Marketing Lecturer Mary Ann Quarton. If airlines embraced the advice of Sarason and Bricker to be more upfront about air travel's potential potholes, they would violate a marketing canon: never introduce negative consequences.

"The whole marketing framework says you find out what the customer wants and you try to give them that," says Quarton.

The Air Transport Association, an industrywide group, declined to comment on Sarason's study for this story. But Cheryl Temple, manager of public affairs for locally based Horizon Air, said her airline already is working to streamline air travel in several ways, including pushing for better airport design and expanding the use of technology. For instance, passengers can now check in and print out their boarding passes from their home computer.

"Things happen," says Temple, "but it's not as frustrating as people generally think—or as the media generally thinks."

Bricker says an airline that prepared passengers for the "things" that happen would win consumer points for honesty.

His interest in air travel was triggered by a stint selling airline tickets at a travel agency during his undergraduate days at the University of California, Berkeley.

"I saw a lot of people under stress," he says.

Chances are Tom Friberg, '70, '76, was not one of them.

When it comes to flight delays and missed connections—two prominent factors on the ATSS—frequent flying has taught Friberg what Sarason and Bricker call "adaptive behavior."

"You've got to roll with the punches," says Friberg, a unit leader and project manager at the Weyerhaeuser Co. "Getting someplace at the expected time, it's a crap shoot. If I get there on time, I won. If I don't, I'll get there sooner or later."

For Friberg, stress is relative. After all, he says, when you've flown out of Afghanistan at midnight to avoid rebel rockets, killing time in a terminal is no big deal.

Besides, says Friberg, people often invite stress by expecting a complex system fraught with variables to work like clockwork every time. He doesn't.

"When you arrive, is when you arrive. Stewing and fussing and fuming about it isn't going to get you there faster."

If Friberg has an "absolute, positive, have-to-be-there meeting" scheduled, "I'll fly the day before. I won't leave it to chance."

He recalls flying to Bangor, Maine, with a trunk full of gear to test some equipment Weyerhaeuser was considering buying.

"I went from here to Denver to Bangor. My gear went from here to Denver to Miami." Fortunately, Friberg flew on Saturday, the meeting was on Monday, and his gear arrived on Sunday.

Besides flying a day early, another way to curb stress is to allow plenty of time between connecting flights—a strategy Sarason both preaches and practices.

During a trip to Europe, he and his wife were scheduled to fly from Barcelona to Frankfurt, where they would catch their flight home. Given a choice between flights arriving in Frankfurt one-half hour before their plane home or 3-1/2 hours, they chose the latter.

Good thing. Their flight from Barcelona was delayed and they would have missed the connection.

"The point is, we made a decision," says Sarason. "We were willing to wait in the airport."

Even so, the temptation to avoid long layovers is strong—a temptation fed by "unrealistic" scheduling by airlines, says Bricker. "They claim that things that go wrong are beyond their control," he says.

|

As part of their ongoing research studies, Sarason and Bricker invite travelers to send e-mail in which they share their air-travel experiences—"not just the problems people have, but what have been the successes," says Sarason. Send comments to isarason@u.washington.edu |

- Return to March 2000 Table of Contents