|

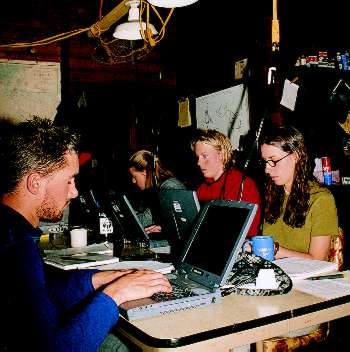

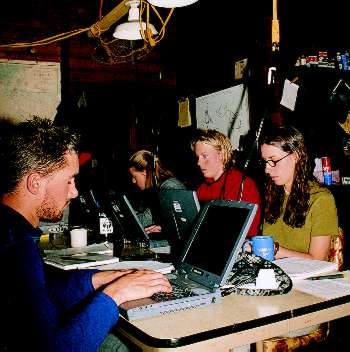

Five students take over the table in the center of the cabin and flip open their laptops. A sixth sits on the vinyl-covered sofa with his computer balanced on his knees.

Homework in the bush did not stop undergraduates from using their laptops. Left to right: Tom Wadsworth, Kristi Overberg, Kirstin Holsman and Mariah Meek.

Their assignment: estimate how many sockeye salmon should be harvested and how many should be allowed to escape and spawn in Alaska's Egegik River. Hard drives whir, computer screens blink and fingers race across keyboards, manipulating data that was recently used by managers making decisions about real fish.

The six undergraduates begin to debate the possibilities. Mariah and Kirstin argue about estimating populations using the Ricker formula vs. the one developed by Beverton and Holt.

Then a student grabs a jacket and a flashlight and makes a one-minute walk to visit the outhouse.

Welcome to the Porcupine Island Field Station, where sophisticated fisheries science meets the Alaska bush.

Alaska is the only place in the United States where scientists can study salmon in watersheds without dams, houses, logging or other human development. These University of Washington undergraduates are doing their homework at the source—in cabins reachable only by boat or floatplane and in streams filled with thousands of flame-red sockeye salmon fighting to spawn.

The students, five from Washington and one from Oregon, are working alongside UW faculty and graduate students for six weeks, building on a half-century of salmon research.

Tom Wadsworth and Kai Chamberlain check a water sample to estimate fish counts.

It is the first-ever undergraduate class offered by the School of Fisheries in Alaska, according to the creators of the course, Tom Quinn and Ray Hilborn, professors of fisheries, and Dan Schindler, assistant professor of zoology. Determined to involve more undergraduates in its world-class research programs, the School of Fisheries received $137,400 from the UW's "Tools for Transformation" fund to do just that. The fund is a special pool of money created by the University to, among other things, serve students in new ways (see Tool Time).

Their Alaskan "classrooms" go back a long way—before Alaska was even a state. In 1946 the federal government asked the UW to investigate declining salmon runs in Southwest Alaska. The UW set up its first research station in 1947 at Aleknagik and has six in all (see map). At that time, the biology of salmon was poorly understood. There were no long-term studies integrating salmon and their ecosystems. So UW researchers developed many basic techniques for counting salmon and understanding their life cycle.

While initially launched to help industry and the federal government understand the size of salmon runs, early leaders of the program such as Bud Bergner, Ole Mathisen and Don Rogers also collected basic information about weather, lake levels, emerging insects, zooplankton levels, other fish species and juvenile salmon growth. It's one of the longest-standing data sets about salmon ecology in the world.

These 54 years of research provide priceless data about the size of salmon populations and basic salmon biology. It's information that's needed to help sort out what might work—and what mistakes to avoid—as policy makers and citizens struggle with endangered salmon runs in Washington, Oregon and Idaho.

|