"It's all about science, politics and money, and not necessarily in that order," Slesin says. "Henry and N.P. had the courage to buck the system, and they have paid dearly for that."

In preparing this article, some industry officials didn't return phone calls asking about Lai's work and the controversy surrounding it. Others said they didn't have specific knowledge of the original study and the events it set into motion-it was more than 10 years ago-but they characterized such research as outside mainstream findings, which they say show that wireless technology is safe.

Still others maintain that possible hazards from recent studies could be discounted because those studies focus on older analog phones, which send out a steady wave of radiation. Newer digital phones operate at a lower intensity, sending out a pulsed stream.

A Swedish study published last fall that tracked 750 subjects who had used cell phones for at least 10 years made note of that difference, and included the following caveat:

"At the time the study was conducted, only analog mobile phones had been in use for more than 10 years and therefore we cannot determine if the results are confined to the use of analog phones or if the results would be similar after long-term use of digital phones."

But it would be a mistake to use that to support a stance that digital phones are proven safe, according to Slesin. The problem, he says, is that pulsed radiation is more likely than continuous wave radiation to have an effect on living things.

"There is a lot of work out there showing that digital signals are more biologically active," Slesin says. "At this point, no one knows whether the enhanced biological activity might compensate for the weaker signals."

Lai, a soft-spoken bespectacled man with an understated sense of humor-he once deadpanned to a national television reporter that the most difficult part of his research involved getting the rats to use tiny cell phones-still expresses surprise at being at the center of the ongoing, swirling debate.

"I'm just a simple scientist trying to do my research," he says. He sees the path that led to controversy as marked by chance and serendipity.

A Hong Kong native, Lai earned his bachelor's degree in physiology from McGill University in Montreal and came to the UW in 1972 to do graduate work. He earned his doctoral degree in psychology and did post-doc work in pharmacology with Akira Horita. His initial research involved the effects of alcohol on the brain. He also worked on a new compound to treat schizophrenia.

A shift came in 1979. Bill Guy, UW emeritus professor and a pioneer in the field of radio wave physics, offered Lai a chance to do research on microwaves through a grant from the Office of Naval Research.

The pair first examined whether microwaves can affect drug interactions (they can), then if there appears to be an effect on learning (there does). Then, in the early '90s, Singh arrived in Seattle. He approached Lai about joining his lab. "He was an expert on DNA damage," Lai recalls. "I said, 'Well, why not?'"

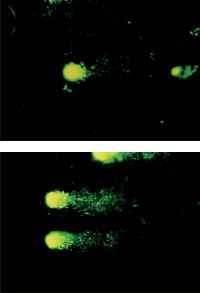

Singh is one of the world's foremost experts on a DNA analysis called the "comet assay." The assay gets its name from the appearance of a damaged cell. First, the cell is set in a gel and "lysed" or punctured. Then an electric current is run across the cell. When strands of DNA break, the broken pieces are charged. The electric current causes those pieces to migrate through the gel. As a result, a damaged cell takes on the appearance of a comet, with the bits of damaged DNA forming the tail. The longer the tail, the more damage has resulted.

With Singh's expertise now at hand, Lai decided to look at how microwaves affect DNA. Lai and Singh compared rats exposed to a low dose of microwave radiation for two hours to a control group of rats that spent the same amount of time in the exposure device, but didn't receive any radiation. The exposed rats showed about a 30 percent increase in single -strand breaks in brain cell DNA compared to the control group.

As Lai and Singh sought funding to conduct follow-up studies, word of the research began to get out. According to internal documents that later came to light, Motorola started working behind the scenes to minimize any damage Lai's research might cause. In a memo and a draft position paper dated Dec. 13, 1994, officials talked about how they had "war-gamed the Lai-Singh issue" and were in the process of lining up experts who would be willing to point out weaknesses in Lai's study and reassure the public. This was before the study was published in 1995.

A couple of years later, Lai got money from Wireless Technology Research (WTR), a group organized by CTIA to administer $25 million in industry research funding, to do some follow-up studies. But the conditions that came with the funding were restrictive. So much so that Lai and Singh wrote an open letter to Microwave News recounting their experience. The letter, published in 1999, cited irregularities in processes and procedures that the two called "highly suspicious."

"In the 20 years or so that we have conducted experiments, for a variety of funding agencies, we have never encountered anything like this in the management of a scientific contract," the two wrote.

Go To: Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4

Inside the Wave: Web exclusive on more cell phone radiation research

Making Waves: Worrisome results from European cell phone study

Old Medicine, New Cure?: Henry Lai's cancer research shows promise