Values drive many physicians to seek a rural practice. On the Idaho side of the Teton Mountains sits Driggs, population 941, and its physician, 1983 UW medical school graduate Larry Curtis. "I want to practice where my patients are my friends," he had told his dad when they drove up from Pocatello to look for an office location.

"I'd never seen Driggs before, but something there clicked for me," Curtis says. He had traveled the world, courtesy of the U.S. Navy. Called up for the draft during the Vietnam War, he worked on submarines, in satellite communications and in jungle survival. A knee injury sent him to the San Diego Balboa Naval Hospital. During recovery, he promised himself he would do what he wanted with his life. While repairing some EKG and X-ray machines, he decided to become a physician.

When he entered medical school, Curtis had a wife and four children (a fifth arrived soon afterward). He says the UW medical school recognized the significance of a student's home life in an eventual practice decision. Curtis wanted to practice in a place where he could be honest with his patients and look out for their best interests.

"If I tell them to quit smoking, they know I'm serious and they don't take it as an imposition," he says.

He also discovered that big-city physicians greatly admire their brethren in the "sticks." "During my WWAMI training I found that most specialists respected rural physicians for their ability to handle many complicated situations. They have to, because they are so far away from advanced specialty hospitals," Curtis says. "At fall harvest, an injured farmer might not want to travel for treatment. He might ask, `Sew me up quick, doc, so I can get back to work.' I talk by phone with specialists in Idaho Falls or at the UW about a plan of care to see if they agree, and then institute it. "

Curtis and his practice partners also use advanced telecommunications, such as two-way interactive video, to contact their colleagues at the UW for medical consultations.

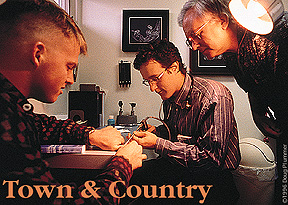

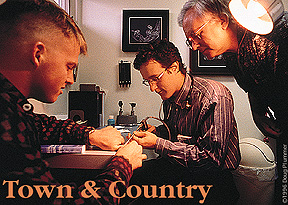

Dr. Ronald

Miller, the WWAMI family practice coordinator in Whitefish, Mont., examines

patient Brian Thramer, while his WWAMI student, Ross Bethel, looks on.

Rice and Curtis have found a good fit: towns that need them and a place where they feel at home. "If physicians are where they feel balanced professionally and personally," says Medical School Associate Dean John Coombs, "they are more likely to stay."

Training doctors for areas with shortages of health professionals and keeping them there is a perennial problem for U.S. medical schools. Coombs explains that new physicians often find it hard to make the transition from university medical centers to practice in an altogether different setting. Many city hospitals have patient census and staffing larger than the population of small Western towns.

Although the country doctor shortage is not as severe as in years past, the demand is still pervasive throughout the rural landscape of the Northwest. The plains, isolated villages and places with geological barriers or harsh weather are hit the worst.

Community Practice Training Once Considered a

"Heresy"

Research Also Part of WWAMI

Training Efforts

Send a letter to the editor at columns@u.washington.edu.