A Civil Action, Part Five: What it Means to be a Citizen

These grim final events obscured from history's spotlight a man who had directly challenged three of America's major barriers against Asians: to becoming a citizen, joining a profession and owning land.

He was too far ahead of his time to be remembered when his battles were finally won. Not until 1952 could Japanese immigrants become U.S. citizens, not until 1965 did Congress put Asian immigrants on par with Europeans, not until 1966 did Washington voters (on the fourth try) repeal the Alien Land Law, and not until 1973 did the U.S. Supreme Court finally grant aliens the right to practice law.

UW History Professor Quintard Taylor. Photo by Kathy Sauber.

This last hurdle—practicing law—was not trivial. Until it was overcome, Asians in many states could never field their own legal team. As UW historian Quintard Taylor points out, many of the major 20th century strides in civil-rights were made by attorneys of color—think Thurgood Marshall—who were themselves victims of discrimination.

"They were first-hand witnesses," Taylor said, "to the disabilities such discrimination placed on their families, friends and communities."

Concerns among Asian Americans today may run more to the government's zeal in prosecuting Los Alamos physicist Wen Ho Lee, but securing the right of citizenship was the primal battle for their grandparents and great-grandparents. The meaning of their struggle reaches beyond one ethnic group. The only way to really understand American citizenship, writes historian Judith Shklar, is to study what it meant "to those women and men who have been denied it and who ardently wanted it."

"This type of story needs to be told," added Tomio Moriguchi, '59, '61, president of Seattle's Uwajimaya supermarket chain and the son of another man who crossed the ocean from Yamashita's hometown.

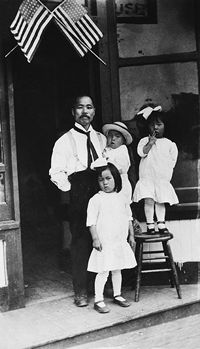

Takuji Yamashita stands in front of a Bremerton storefront with three of his children in this photo probably taken on the Fourth of July. The children are Joe (hat), Martha (on stool) and Aya (standing). Photo courtesy of the Takuji Yamashita Photograph Collection, University of Washington Libraries.

It wasn't just time that hid Yamashita's story, but also the space between continents. His Japanese daughter, Haruko, and her descendants knew little of his U.S. exploits. Little, that is, until Haruko's grandson, Naoto Kobayashi, married an American and, in 1993, moved to Maine. The move sparked his curiosity about the ancestor who'd sailed to America so long ago.

"It was exactly 100 years since Takuji Yamashita came to America, and my wife was pregnant at the time," Kobayashi said. "I felt some kind of destiny."

He and his sister, Tokyo sociology professor Tazuko Kobayashi, began piecing together their great-grandfather's story with Magden's help and through pilgrimages to such sites as the Togo Hotel and University of Washington.

Takuji Yamashita never got to be a full American. But he has a great-great-grandson growing up in Maine, named Takuji. The boy speaks a little Japanese.

Steven Goldsmith is a writer in the UW Office of News and Information and was formerly a reporter for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

| On the Web: HistoryLink.org Timeline entry |